Culinary heritage of wetlands

Although considered mystical and potentially dangerous, wetlands have since pre-historical times been amongst the first places where people choose to live. They have done this for a number of reasons: the wetlands offered protection against fires, animals and other people, they were used for transport, and they often held a sacred character as places where people came closer to gods and spirits. Above all, they were necessary for survival: wetlands were, and are, sources of clean water and food.

Wetland systems encompass food chains, providing an abundance of plants which form the basis of the food chain and are eaten by herbivores (mice, rabbits, deer, insects, fish, ducks and other waterbirds); these are then eaten by secondary consumers (birds of prey, snakes, foxes, fish, wild cats), which in turn are eaten by tertiary consumers (turkey, vultures, and people)! For thousands of years people chose to establish their settlements near to wetlands so that they could enjoy abundant fish and hunt the animals that frequented the wetlands to drink water or find their next meal.

Typical food associated with wetlands includes rice, fish and related products and game. These kinds of food nurtured people living around wetlands and comprised part of their gastronomic heritage, distinct for each area and characteristic of their particular culture. The ingredients people use in their food, how they combine and cook them, and the way they share them (different for each occasion, everyday or special) give significant insights into local beliefs, customs and social organisation.

Famous dishes (such as the paella that forms a part of certain regional cuisines) did not enjoy much respect in the past. Instead, they were considered poor and uninviting. Moreover, as a result of industrialisation, artisan production was threatened and traditional techniques abandoned. In the 20th Century this trend was reversed, rural space gradually became linked with health, place-based identity came to be considered heritage and local traditions were promoted. Today, in the age of tourism, food has become a major part of the anticipation of pleasure for travellers and an important reason to visit particular places.

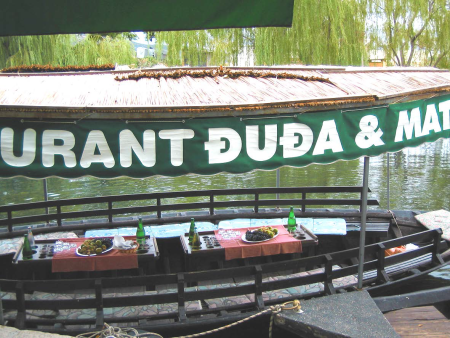

Today, travellers seek authenticity, and nothing can compare to the authenticity of traditional, local food, which allows visitors to get a taste (literally) of local culture. Many wetland sites, such as the Neretva Delta in Croatia, have incorporated traditional local dishes in eco-tourist products, helping to boost the local economy.

Food has often been considered sacred, because it feeds and sustains humans and is produced by human labour, which can be considered sacred in itself. It satisfies more than material hunger. Food is central to a profound social urge: it is usually shared, making food a focus of symbolic activity and mutuality, and forming a foundation for communication between family members and within a community.

Wetland food is the element that symbolically connects humans and their culture with the natural world. For these qualities, it can be considered as one of the best ambassadors for wetland conservation, as healthy food can only be produced by healthy wetlands.

Irini Lyratzaki (Scientifc Secretariat, MedINA)

Irini Lyratzaki was born in Heraklion, Greece. She holds a BSc in Economics and Tourism, a BA in Social Anthropology and Social Policy and a MSc in Landscape, Environment and History. She worked in the tourism sector for several years and later as an Anthropologist in the Museum of Cretan Ethnology. Since 2004 she has been working for Med-INA as a member of its Scientific Secretariat, managing cultural content, undertaking research, organising scientific meetings and coordinating publications and projects. Most of her job relates to the field of cultural values of wetlands and sacred natural sites.